How To Read Piano Sheet Music

Are you having a hard time learning how to read piano sheet music?

Are you having a hard time learning how to read piano sheet music?

Are you one of those piano students who’s like, “I wanna play but I find reading notes taxing and frustrating?”

Guess what: This lesson is for you.

In this lesson, you will discover how to make sense of reading notes.

Let’s get started.

5 Reasons Why You Want To Learn How To Read Piano Sheet Music

Now, a lot of people can easily argue that they can play music without learning how to read notes.

Now, a lot of people can easily argue that they can play music without learning how to read notes.

That is true. However, there are many of great reasons why you should learn how to read piano sheet music.

Here are 5 compelling reasons:

- It helps you understand music better than by just playing by ear. Written music allows you to dissect how music works easier.

- Learning how to read piano sheet music helps you learn music faster. It simply takes the guesswork of what to play in most music.

- With that being said, learning how to read piano sheet music helps you play more accurately.

- Reading music gives you access to plenty of ideas. Centuries worth of valuable musical knowledge from all over the world are written in standard notation. To grow as a musician and learn new ideas, you need to first tap into a pool of more than a generation’s worth of knowledge all preserved via notation.

- Learning how to read and write in standard notation helps you communicate musical ideas clearly and more accurately with other musicians. The reason why we call it standard notation is that the notation we now see has been the de facto standard for written music for centuries. Majority of professional and amateur musicians read and write standard notation, and so it’s an effective way of sharing musical ideas.

Now that we have identified some reasons, let’s get into building your music reading skills.

What Piano Sheet Music Looks Like

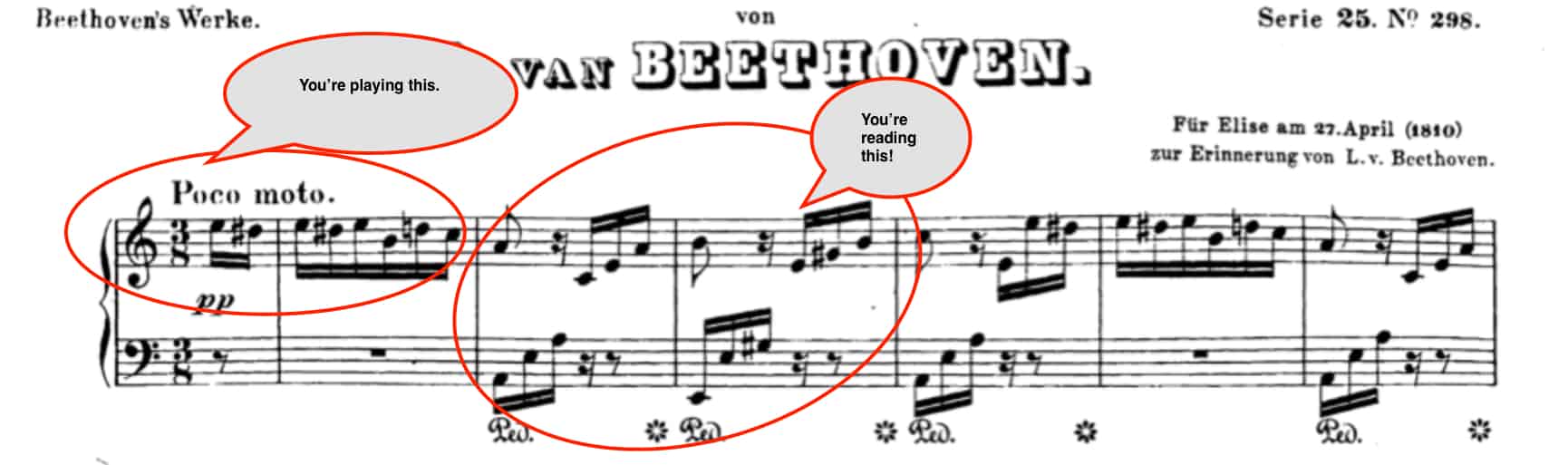

As most people easily discover, piano sheet music looks something like this:

What we have above is called the grand staff.

At its most basic, standard notation on the grand staff shows:

At its most basic, standard notation on the grand staff shows:

- How big are each measures (meter or time signature)

- When to play and not to play notes (rhythm)

- How high or low to play notes (pitch)

- What predominant scale the piece uses (key signature)

- How loud or soft to play notes (dynamics and articulation)

- The overall structure of the piece (form)

These are only a few of what you need to learn how to read piano sheet music.

Why Begin With The Beat When Learning How To Read Piano Sheet Music

The biggest problem you find when learning how to read piano sheet music is rhythm.

The biggest problem you find when learning how to read piano sheet music is rhythm.

Let’s try and dissect that by talking about the beat.

What exactly is a beat?

Musically speaking, a beat is a unit of musical event that happens at a specific time.

For example, try feeling for your heartbeat or pulse.

Every time your heart beats, it’s an event that happens at a specific time at a regular interval.

This is where we get the concept of a musical beat.

Everything in music is bound to the beat. This is why we start learning how to read piano sheet music by understanding it.

The beat is the foundation for how plot musical events in time.

Try this exercise: If you have a clock, try clapping or stomping your foot one second at a time.

If you do this, now you have what resembles a musical pulse.

To be even more specific, go ahead and grab a metronome. Use any version of it, whether online, app, or physical.

To be even more specific, go ahead and grab a metronome. Use any version of it, whether online, app, or physical.

Set your metronome to 60 BPM and then clap or stomp your foot for every click.

By doing so, you are playing a beat at a specific time.

The beat now becomes a reference for how you plot out sound and silent events to create music.

It’s also a measure of how long or short a sound or silent event is.

Now that you understand what a beat is, let’s see how we can use that.

How To Map Out Beats On Paper

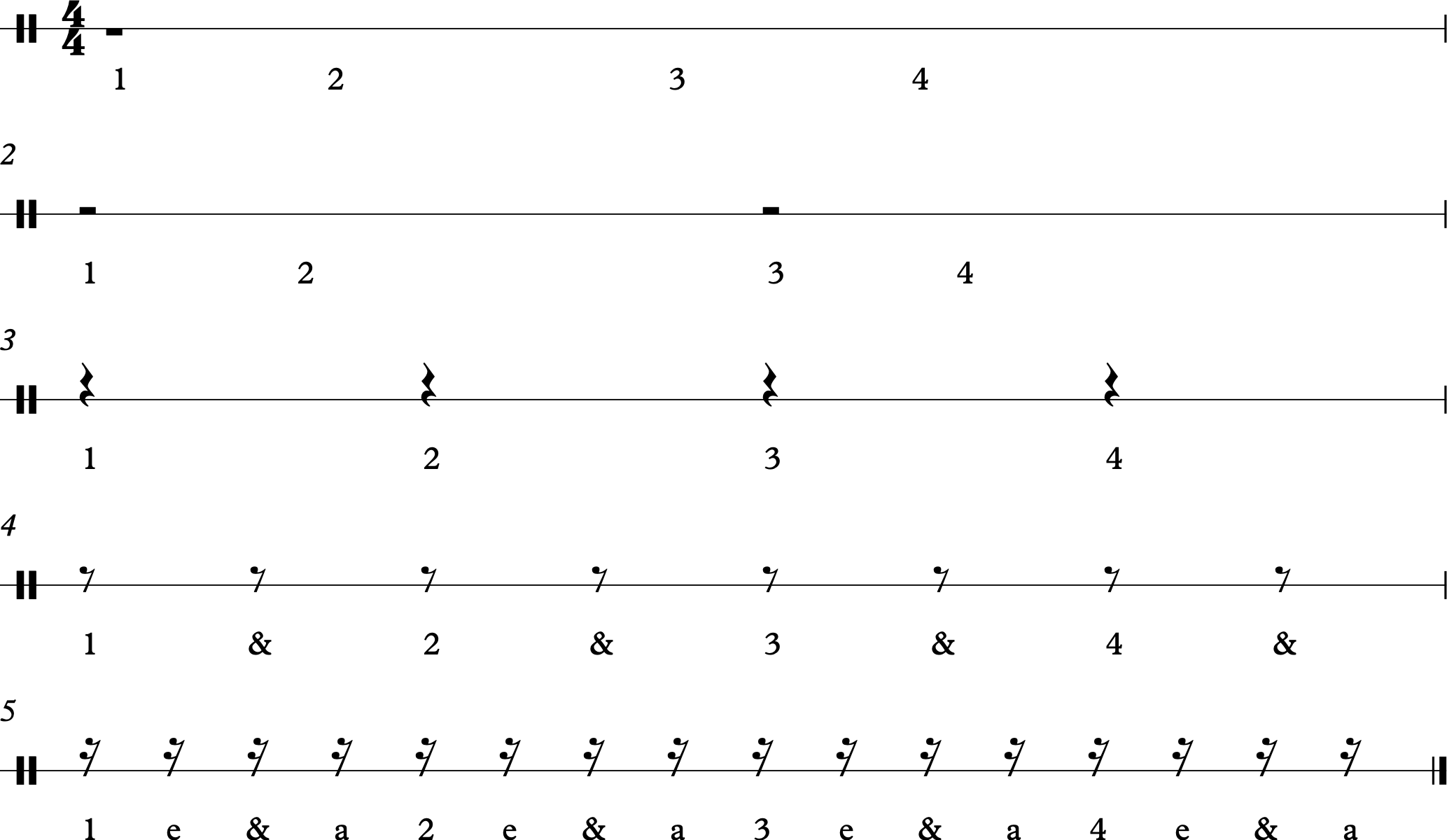

To map out musical events on paper, we can simply plot them in a timeline.

To map out musical events on paper, we can simply plot them in a timeline.

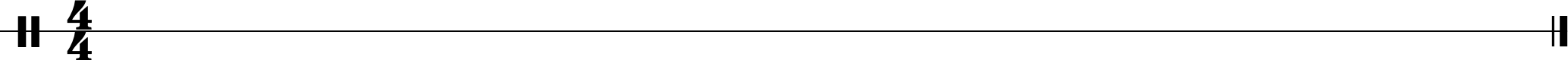

In music, we call this timeline the staff:

For the meantime, our staff only has a single line.

The staff is where we can plot our notes (sound events) and rests (silent events).

As you might have guessed, notes and rests can be long or short. This is what makes up rhythm.

However, how do you figure out how long or how short a note is?

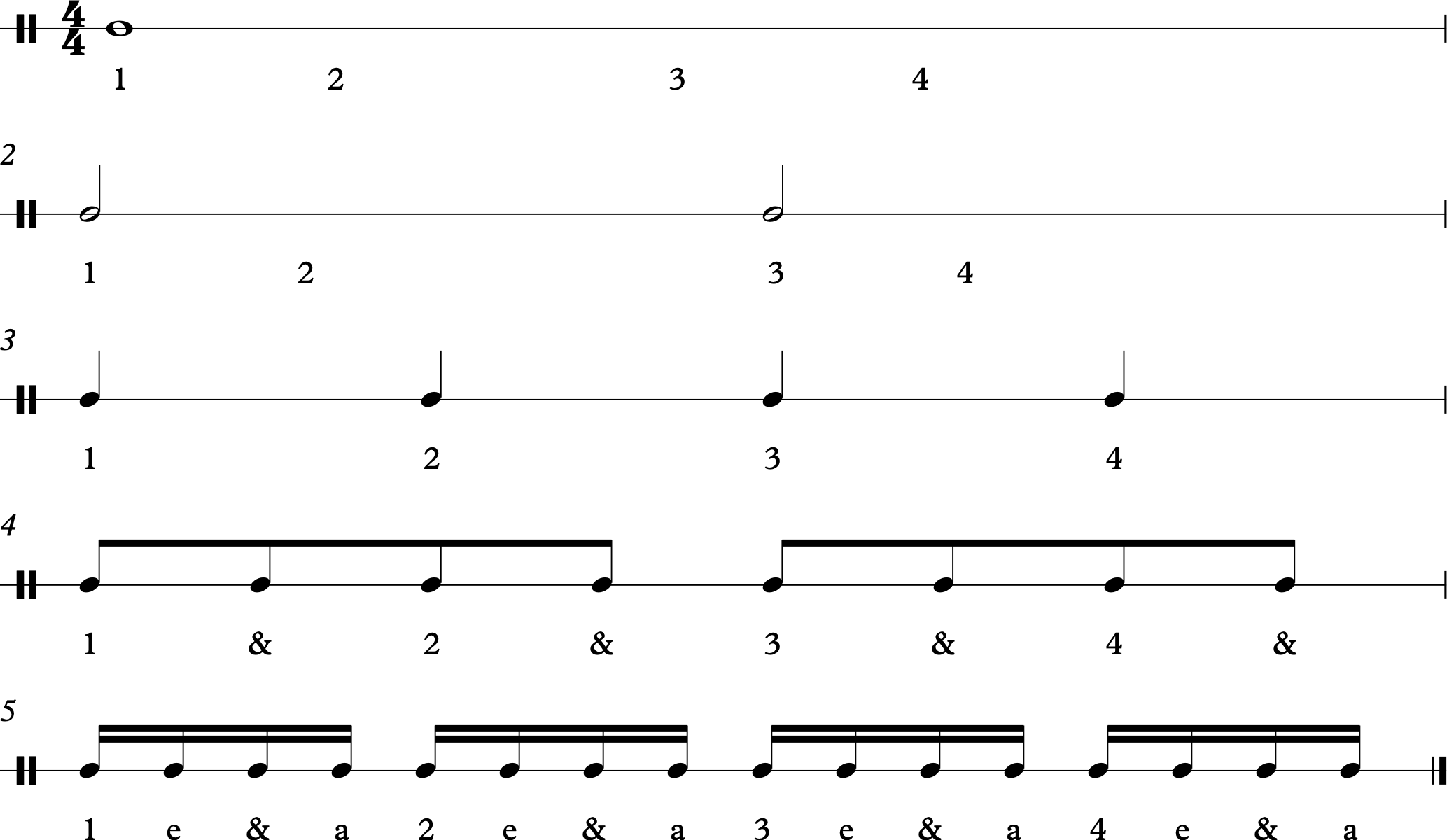

How To Figure Out Rhythm Using Beats When You Learn How To Read Piano Sheet Music

The beat is the basic unit of measurement in music.

We tend to measure how long or how short a note sounds using the beat.

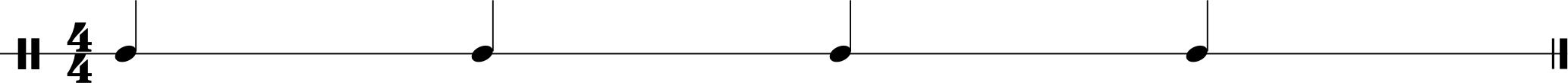

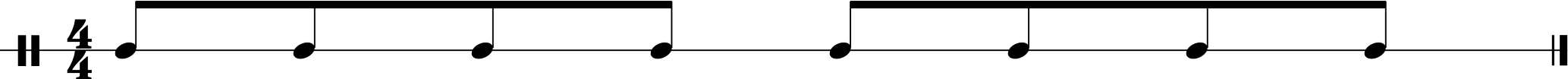

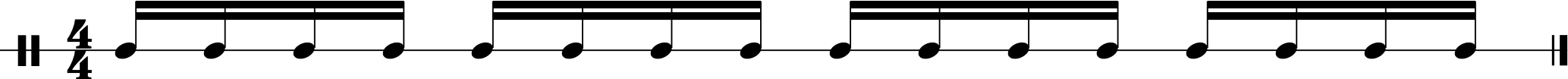

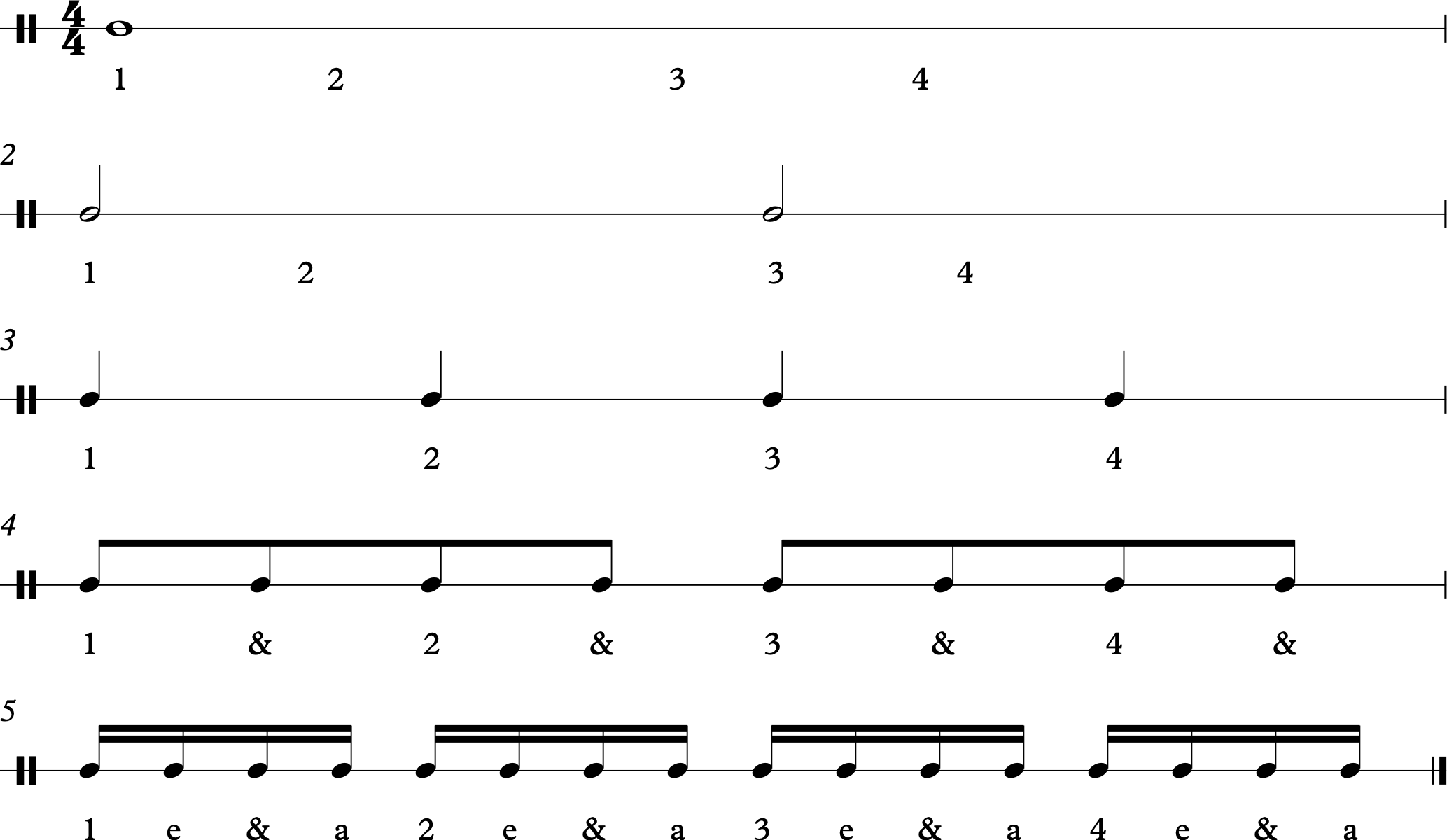

In most music, the quarter note lasts 1 beat long.

As seen above, we plot those quarter notes along the staff (our timeline).

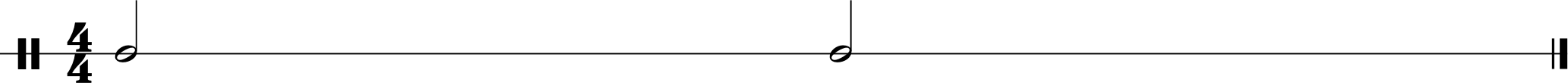

We also have notes that are longer or shorter than a quarter note.

- A whole note is 4 beats long

- A half note is 2 beats long

- An 8th note is 1/2 beat long

- A 16th note is 1/4 beat long

From here, it’s easy to build something we call a rhythm tree to see this relationship:

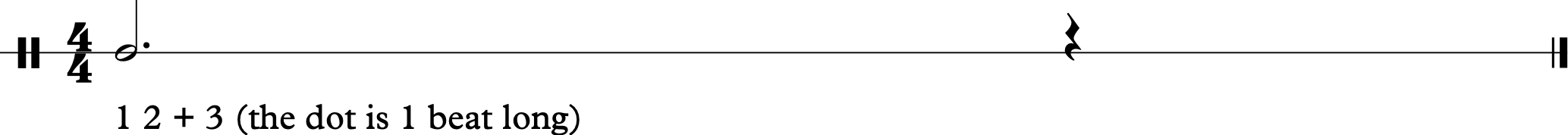

Dotted notes sound longer. The dot adds half the length of the original note. For example, a dotted half note lasts 3 beats long:

Surely, we can write rhythms using various combinations of long and short-sounding notes along the staff.

Now that you know when to play, how do you know when you’re supposed to be silent?

Why Rests Are Important When Learning How To Read Piano Sheet Music

Symbols we call rests tell us when to be quiet.

Symbols we call rests tell us when to be quiet.

Imagine being talked over without pauses for even a breath.

Music without rests are just as annoying.

Remember the basic definition of music being an organized arrangement of sounds and silences that’s pleasing to the ear?

Rests are necessary in music. And so, this is why we notate them too.

Rests have the same beat values as notes:

- A whole rest is 4 beats long

- A half rest is 2 beats long

- An 8th rest is 1/2 beat long

- A 16th rest is 1/4 beat long

Now that you understand notes and rests, you can now attempt to navigate written music.

The problem is, if we plot too many of these along our staff, it’s going to be hard to navigate.

Let’s learn how to get it more organized.

Why You Need Bars And Time Signatures

To make sheet music easier to read, you need to cut up the staff into bars.

To make sheet music easier to read, you need to cut up the staff into bars.

Cutting up the staff into bars helps us organize written music in smaller sections.

The thing about using bars in sheet music is that we need each bar to contain the exact number of beats.

And so, how do we do that?

We have to use time signatures to know how many beats we have inside each bar.

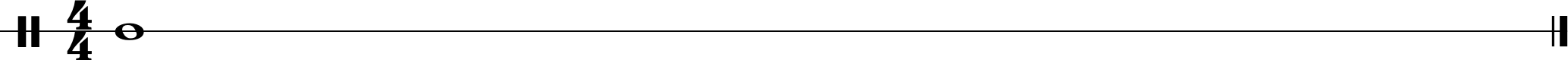

You can find a time signature at the beginning of your sheet music:

You can see 2 numbers:

- The top number tells us how many beats there are per bar.

- The bottom number tells us what kind of note receives the beat.

In the example above, 4/4 means that we have 4 beats that are quarter notes (4).

In the example above, 4/4 means that we have 4 beats that are quarter notes (4).

Interestingly, any kind of note might receive the beat.

For example, there are pieces of music that have 4 half note beats per bar (4/2), 6 eighth note beats per bar (6/8), 15 sixteenth notes per bar (15/16), etc.

Incidentally, there are 2 main reasons why composers use various time signatures:

- Readability

- Feel

For the most part, however, the most common time signature in contemporary music today is 4/4 time. 3/4 and 2/4 time are also very common.

It’s for this reason that 2/4, 3/4, and 4/4 time are called simple meters.

Now you might ask, what’s meter?

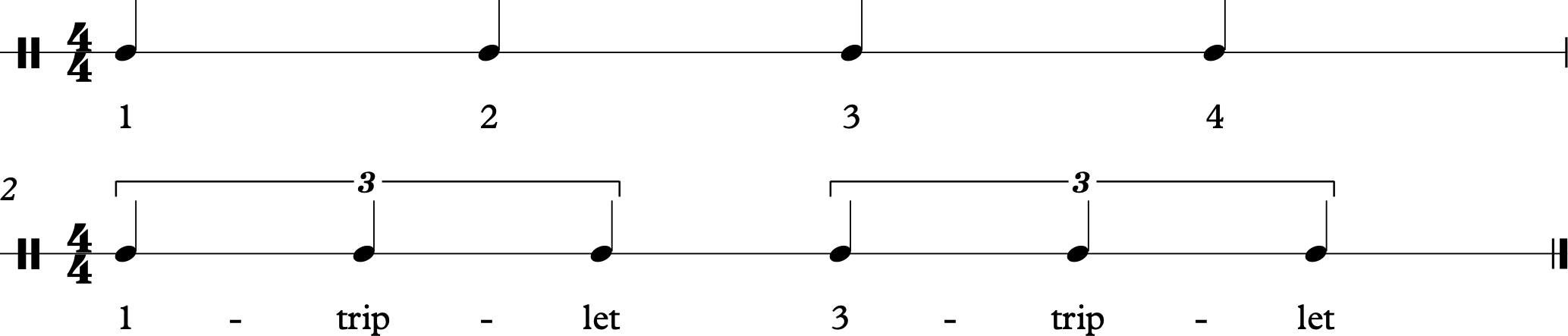

What Is Simple Meter?

Given the name, simple meter is one of the easiest to understand when learning how to read piano sheet music.

Given the name, simple meter is one of the easiest to understand when learning how to read piano sheet music.

This is because we’re simply counting quarter note beats no more than 4 beats per bar.

Here are the three simple meters:

- 2/4 a.k.a. simple duple meter – 2 quarter note beats per measure. Common in punk, thrash metal, ska, and polka.

- 3/4 a.k.a. simple triple meter – 3 quarter note beats per measure. This is the meter for waltz music.

- 4/4 a.k.a. simple quadruple meter – 4 quarter note beats per measure. The most common meter in most contemporary music such as rock, pop, jazz, blues, metal, etc.

So, when we’re keeping track of music, we count meters in different ways. For example, we count beats on duple meter as 1-2, triple meter as 1-2-3, and 1-2-3-4 for quadruple meter.

Now you might be thinking, “What’s the difference between 2/4 and 4/4?”

Great question. You’ll find out below.

Why Accents Matter When Learning How To Read Piano Sheet Music

Traditionally speaking, the 1st beat is the strongest beat. When you learn how to read piano sheet music, the 1st beat of every bar is accented or stressed.

Traditionally speaking, the 1st beat is the strongest beat. When you learn how to read piano sheet music, the 1st beat of every bar is accented or stressed.

So, if we listen to 2/4, we hear alternating strong and weak beats. When we count, it’s going to sound like ONE-two, ONE-two, etc.

When we listen to 4/4, the strong beat is followed by the weaker 2nd, 3rd, and 4th beats. It sounds like ONE-two-three-four.

Accents in musical meter matter because the way we place accents in beats or notes directly contributes to the feel of the music.

For example, a fast song like Metallica’s “Hit The Lights” feels different from “Every Breath You Take” by the Police.

Now that we have a basic understanding of accents, let’s talk about groups of threes.

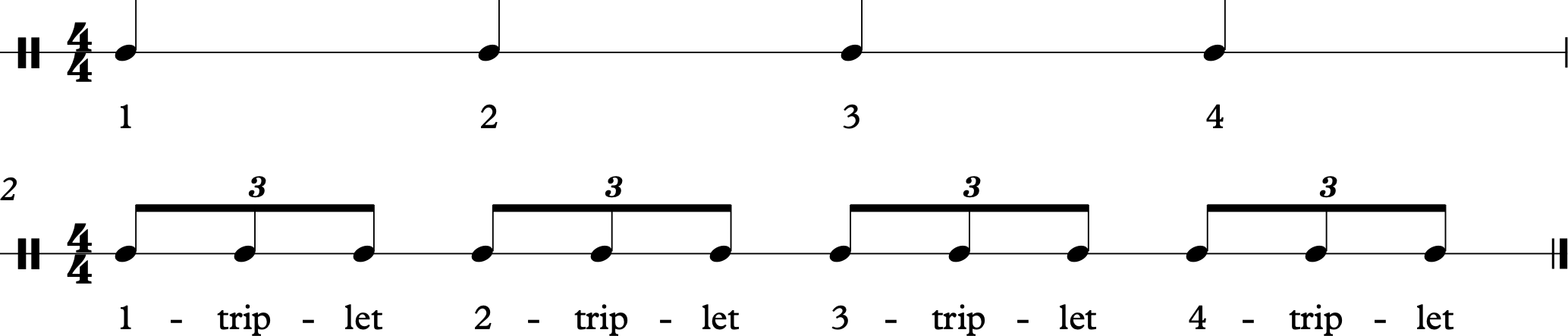

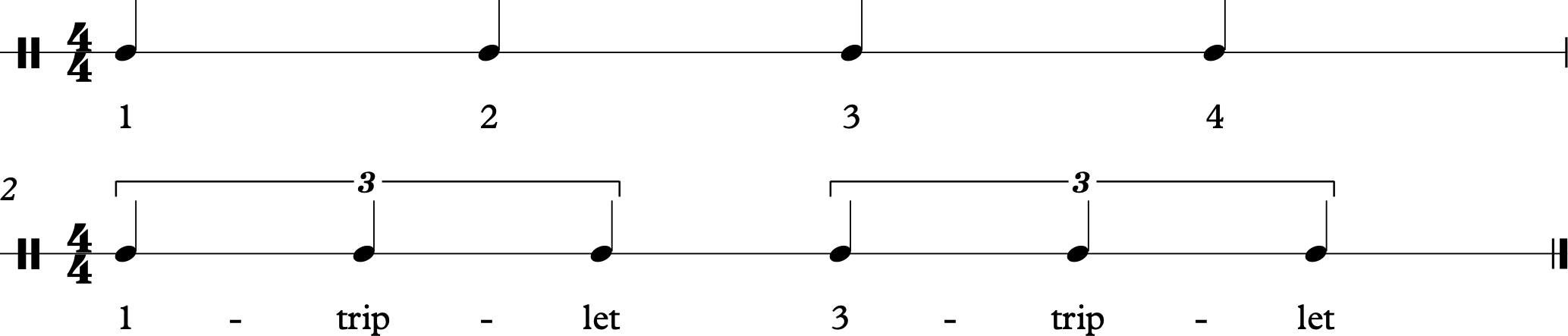

How To Read Triplets

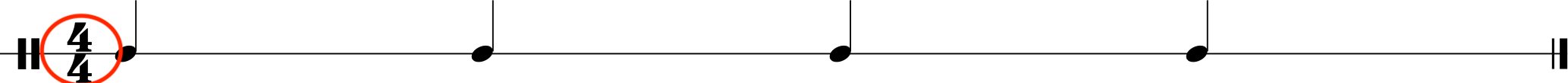

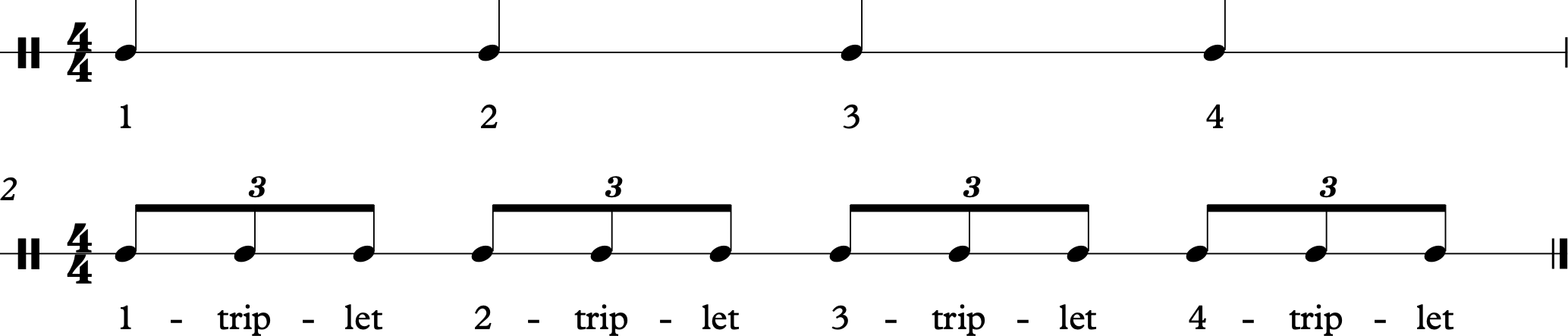

When learning how to read piano sheet music, we often start learning rhythms in beat multiples or subdivisions of 2.

When learning how to read piano sheet music, we often start learning rhythms in beat multiples or subdivisions of 2.

For example, 1 whole note = 2 half notes = 4 quarter notes = 8 eighth notes = 16 sixteenth notes.

Refer to the rhythm tree above to see how multiples or subdivisions of 2 work in rhythms.

However, it’s also fairly common to subdivide the beat into 3 or group 3 notes in the space of 2 beats.

These are what we call triplets.

The easiest way to look at a triplet is to fit 3 eighth notes in the space of 1 beat:

Another kind of triplet you will encounter is the quarter note triplet. It’s three quarter notes fit into the space of two beats (or a half note):

Now that you know about beats, rhythm, and meter, let’s look into actual strategies how to read and play them.

How To Read And Play Rhythms With Syllables

There are a number of ways we learn how to read and play rhythms. Interestingly, we can make use of various systems such as:

There are a number of ways we learn how to read and play rhythms. Interestingly, we can make use of various systems such as:

- The beat number method

- Kodaly Method

- Konnakol (a South Indian tradition)

- Gordon Music Learning Method

To keep track of meter, we’re going to use the beat number method.

Here are a couple of guidelines:

- We count the beats using numbers per bar. For example, we count 4/4 as 1-2-3-4, 3/4 as 1-2-3, etc.

- Any note that receives the beat is designated the number. For example, in 4/4, we count quarter note beats 1-2-3-4.

- When we subdivide the beat into 2, we recite the number followed by “&”. In 4/4, we count eighth notes as 1-&-2-&-3-&-4-&.

- Subdividing the beat into 4 means we count the first note of the beat with a number and then use “e-&-uh” as the next four. In this case, 16th notes in 4/4 means we count them 1-e-&-uh, 2-e-&-uh, 3-e-&-uh, 4-e-&-uh.

- To count triplets, we recite the number for the note on the beat then “trip-let” for the 2nd and 3rd notes. So, in a measure of 4/4,we count triplets as 1-trip-let, 2-trip-let, 3-trip-let. 4-trip-let.

Let’s review our rhythm tree to see these syllables in action:

You can start practicing by counting along the clicks of a metronome. One of the best metronome apps for this purpose is the Metronome by Soundbrenner.

Let’s apply this concept to figure out how to play the rhythm for “What A Friend We Have In Jesus”:

Another great app you can use to learn how to read rhythms is Rhythm Lab.

To get started, look for rhythm drill sight reading materials via Google to practice reading and playing rhythms.

How To Practice Reading Rhythms With Your Piano

With certainty, we can say that learning how to read piano sheet music should start at the piano.

With certainty, we can say that learning how to read piano sheet music should start at the piano.

This is why we’re going to apply reading rhythms while we’re seated at the piano.

Here are the steps:

- Prepare your rhythm drill sheets and set them on a music stand.

- Set up your metronome to a manageable tempo. A manageable tempo means a slow tempo that’s not too difficult to work with.

- Read your rhythm drill. Recite the rhythm using rhythm syllables to outline it in your mind.

- Turn on your metronome and recite the rhythm drill with rhythm syllables.

- Once you can recite the rhythm accurately, close the lid of your piano and tap using both hands.

- Open the lid of your piano and play the rhythm drill over any note or chord while still reciting the rhythm syllables.

Surely, it can be easy to deal with rhythm drills when the tempo is slow. But what if things get crazier? What do you do?

Find out the answer below.

Why Reading Ahead Is Important

One of the most important things in learning how to read piano sheet music is reading ahead.

As the term implies, reading ahead means reading in advance a few beats or measures ahead of what you are playing.

This is one of the keys to coping with any tempo when sight reading.

Here’s how to practice reading ahead:

- Read your sheet music. Try to imagine the sound of the notes you are reading in its correct tempo.

- Begin playing by reading at leas the 1st 2 beats up. You can read more than just 2 beats once you get used to this process.

- Start playing what you’ve read before while reading the next 2 beats.

- Repeat the process.

Being able to read ahead will work wonders on how you read piano sheet music.

Now that we’ve dealt with rhythm, let’s learn how to read pitch.

How To Know If It Sounds High Or Low

Other than learning how to read rhythm, you need to learn how to read pitch.

Other than learning how to read rhythm, you need to learn how to read pitch.

Pitch is simply how low or high a note sounds.

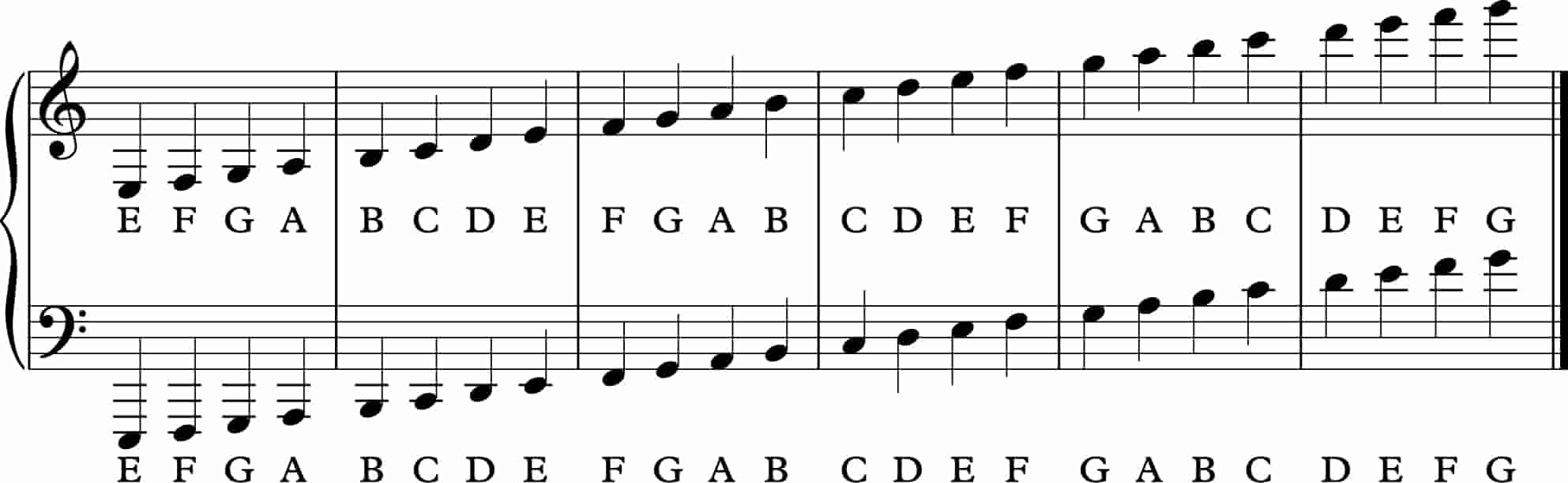

To represent this on paper, we now have a five-line staff:

The pitch of the note depends on its position on the five-line staff: The higher it is on the staff, the higher the pitch, and the opposite is true.

It’s really that simple.

In terms of reading piano sheet music, the higher the notes are on the staff, the nearer they are to the right side of the piano.

To really know our notes, you need to know their names.

How To Name Notes

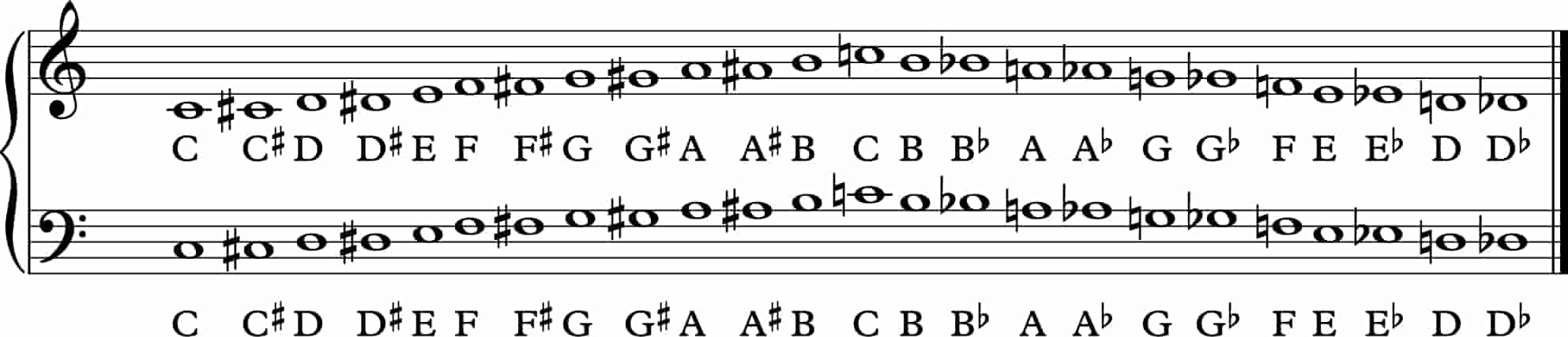

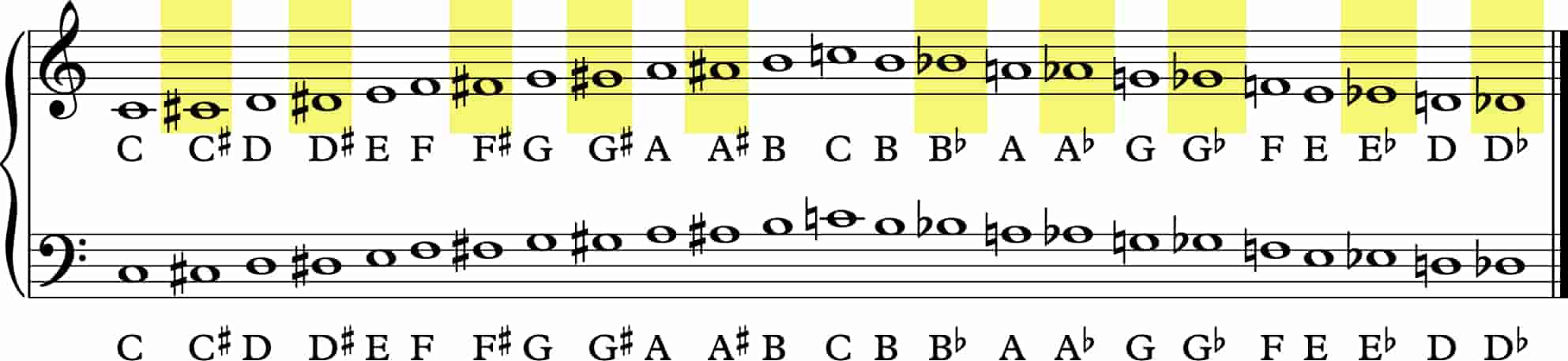

In western music, we have 12 notes:

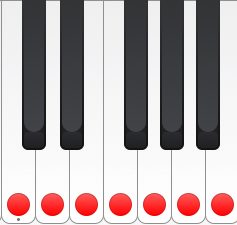

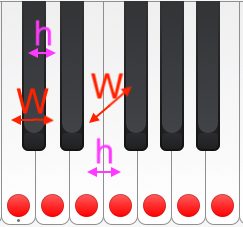

We assign the letters A, B, C, D, E, F, and G for naturals (the notes on the white keys). The notes on the black keys (a.k.a. accidentals) have their names based on their relationship to the white keys.

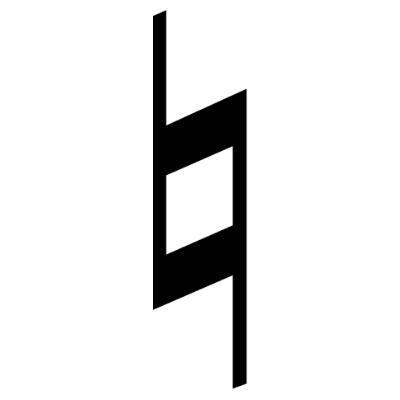

A black key can either be a sharp or flat. If it’s a black key to the right of a white key, it’s a sharp (#). If it’s a black key to the left, it’s a flat (b).

To make things simple at first (piano-wise), we tend to learn that there are no sharps after B and E and there are no flats before C and F. From a more technical music theory perspective, this is not true as we’ll explain later.

Interestingly, one note can have 2 different names. These are what we call enharmonic names.

For example, C# and Db are the same note on the piano keyboard. The same black key is to the right of C natural (and so it’s C#) and is to the left of D (therefore Db).

Whenever we see accidental symbols, they remain in effect all throughout the measure it’s applied to.

In cases where the key of the song has

That’s fine and dandy. However, we still have a problem.

How can we tell which notes are which on the staff?

This is where clefs come in.

How To Use Clefs

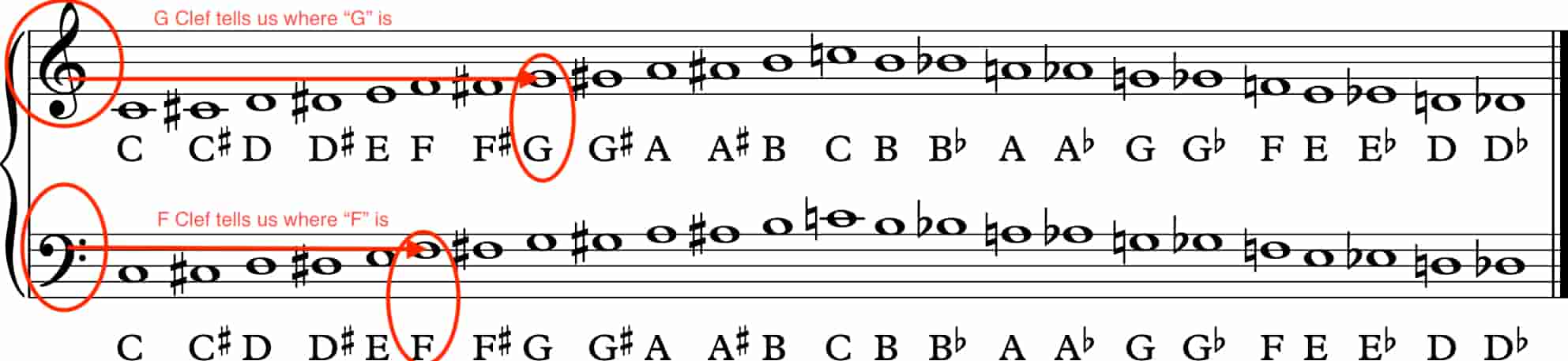

Do you see those fancy, curly looking symbols in front of the first measure? Those are clefs.

A clef tells you the specific note of a line in the staff. That way, you have a reference for every other line in the staff.

When we start learning how to read piano sheet music, we make use of 2 clefs on each stave.

The upper staff has the G clef.

The G clef points to where the note G is on the staff. As you can see, the second line passes through the heart of the G clef.

Since we have that G on the 2nd line of the staff, we now have a reference point for pitches. Adding the G clef to the staff also turns it into a treble staff i.e. notes in the treble range are written here.

Let’s now look at another kind of clef called the F clef.

As seen below, the F clef is used for showing pitches along the bass register:

As you can see in the image above, the line passing through the 2 dots of the F clef is the note F. It now provides us a reference point for every pitch in relation to this F.

If the notes go below or beyond the lines of the staff, we use leger lines as imaginary placeholders to represent the pitch:

Now let’s go into sets of notes that tend to sound great together.

The Major Scale And Key Signatures

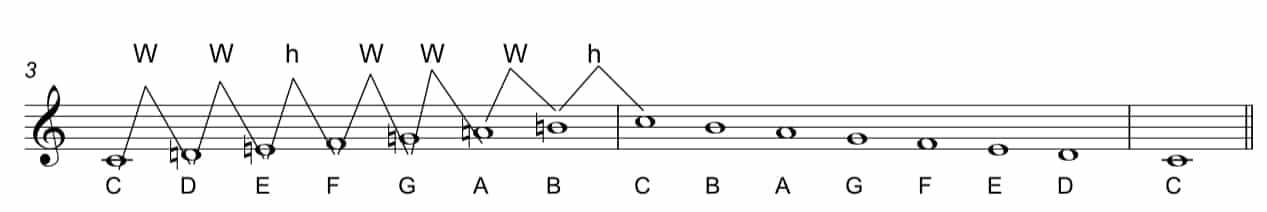

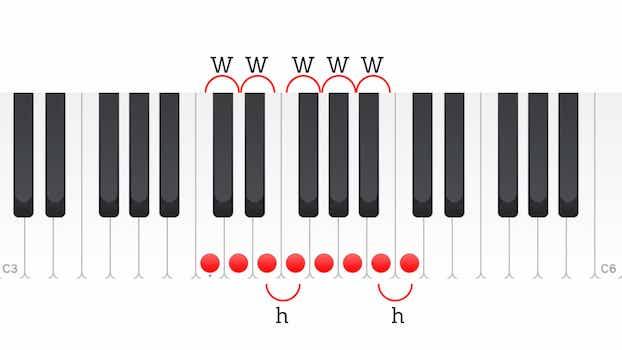

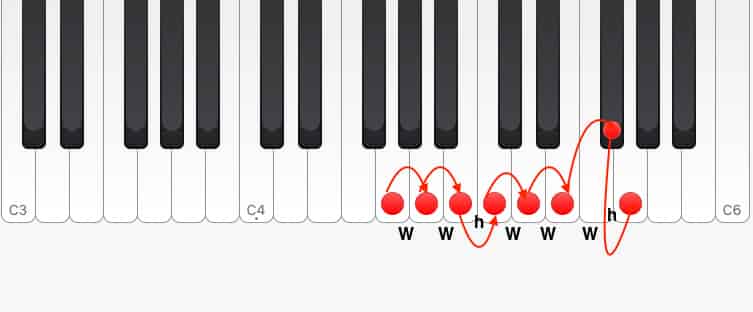

Do you see all the white notes of the keyboard? These white notes form what’s called a major scale:

Now you might ask, how did people determine these 7 pitches to be the major scale?

We define a major scale by a specific set of intervals. All 7 notes in a major scale are one whole step apart except between the 3rd and 4th and the 7th and octave (these notes are separated by a half step).

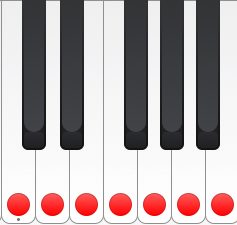

Refer to the image below to understand quicky what whole and half steps are:

Think about whole and half steps this way:

- A half step are 2 piano keys directly beside each other (For example, C# to D or E to F).

- A whole step are 2 piano keys separated by a key in the middle (think C to D or E to F#).

The scale we have here is a C major scale. These are all white notes. E and F are separated by a half step and so does B and C.

Again if we look closely at the C major scale, here’s the sequence of intervals in between each note:

C (W) D (W) E (h) F (W) G (W) A (W) B (h) C

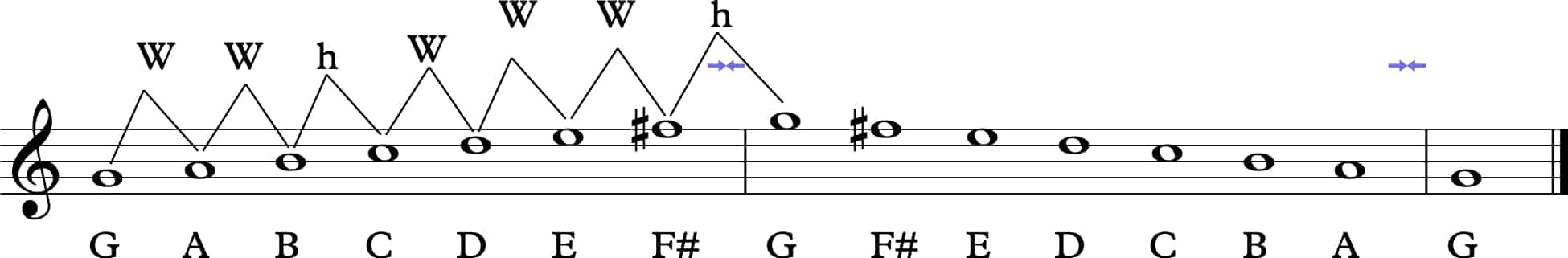

Now, if you are to start a major scale at a different note, you need to use the same set of intervals but this means that the notes will change.

For example, if we have a G major scale, we have these notes and intervals:

G (W) A (W) B (h) C (W) D (W) E (W) F# (h) G

Since a song in the key of G will have that F# most of the time, it can be tedious to write every F# over the sheet music. And so, composers just write a sharp (#) over the line for F which means that you have to play all F’s as # unless indicated by a natural sign:

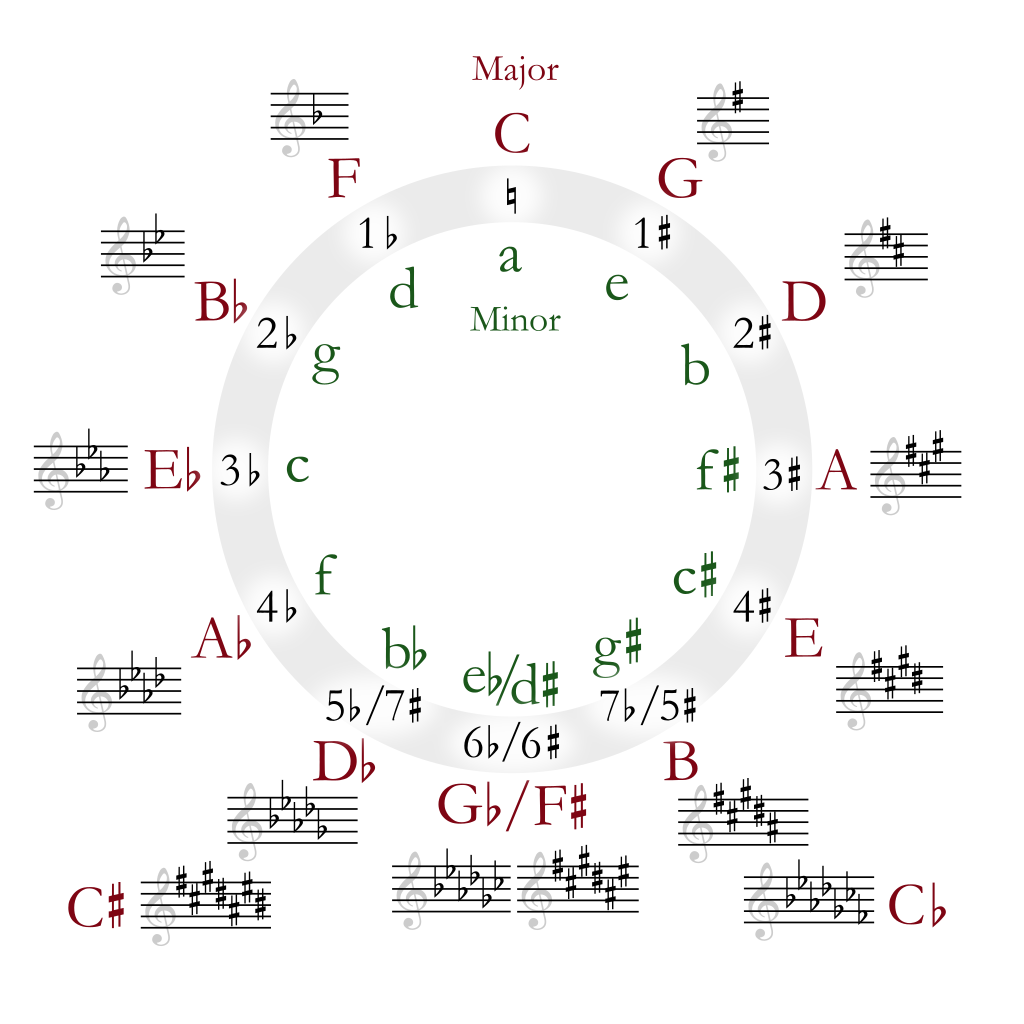

Given that all major scales have different sharps and flats assigned to them, we now have what we call key signatures. We have listed them all in here based on the number of sharps and flats they have:

C – no sharps or flats

G – #

D – ##

A – ###

E – ####

B – #####

F# – ######

C# – #######

Cb – bbbbbbb

Gb – bbbbbb

Db – bbbbb

Ab – bbbb

Eb – bbb

Bb – bb

F – b

To easily remember the list above, music theorists have devised the concept of circle of 5ths:

“Circle of fifths. A trick to find the flats in a scale is to look on the second flat to the last – if they are in correct order on the staff” by Just Plain Bill is licensed under CC BY 4.0

For more details about major scale theory and chords, go to this piano chord theory lesson inside Freejazzlessons.com.

How To Know When To Play Loudly, Softly, Or With Accents

Learning how to read piano sheet music is not just about pitch and rhythm.

Learning how to read piano sheet music is not just about pitch and rhythm.

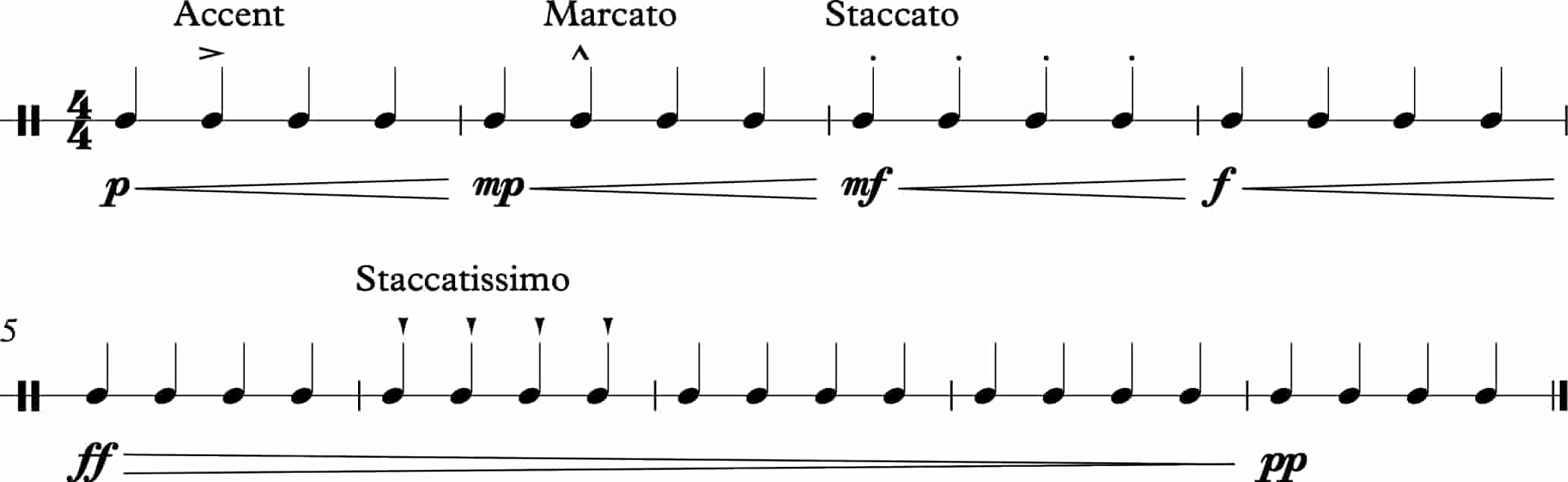

You also need to understand when to play loud or soft. The loudness or softness of sound (in terms of volume) is called dynamics.

Other than rhythm, a combination of loud and soft sounds creates an impression of groove, phrasing, contrast, and interest.

Let’s look at some common dynamic markers:

- p – stands for piano, which is Italian for “soft”. The term pp means “pianissimo” or very soft. The more “p”s you put in place, the softer the sound.

- mp – stands for “mezzo piano” or “moderately soft”.

- f – “Forte” means “loud”. “Fortissimo” or ff means “very loud”. The more “f”s you place, the louder the sound is.

- mf – is “moderately loud”.

In many cases, dynamics are relative. However, it’s safe to say that these dynamics were developed in reference to acoustic instruments.

Other kinds of dynamic markings you might see when learning how to read piano sheet music include:

- Hairpins – A crescendo marking goes from soft to loud over a particular phrase or set of notes. A decrescendo or diminuendo marking goes from loud to soft.

- Accent marks – small, hairpin-like articulation mark instructing you to play a particular note loud.

- Staccato and staccatissimo marks – Play the note short. More accurately, play the notes in a passage disconnected from each other, the opposite of legato where you play all notes connected together.

Now that you know sufficient details for reading sheet music, let’s look at methods how to practice it.

How To Practice Reading Piano Sheet Music

The best way to continue learning how to read piano sheet music is as follows:

The best way to continue learning how to read piano sheet music is as follows:

- Pick very easy piano sheet music to practice reading. Let’s say you’re already quite advanced as a piano player, pick music that’s about 5 levels lower than what you can actually play. This is because you want to have that success at the beginning.

- Clap or tap the rhythms over each staff first before playing. If you’re reading a treble or G clef staff passage, tap with the right hand. Conversely, tap with your left hand if you’re reading the bass staff (F clef).

- At the start of your sight reading journey, start playing from sight by using just one hand at a time. If that is already too easy, start playing hands together while reading the music.

- Remember to read ahead i.e. read a few notes or even a bar in advance of what you’re actually playing. Learning how to read ahead helps you play in time.

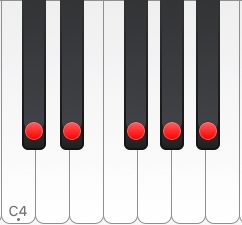

- Learn how to navigate the piano keyboard through feel rather than sight. Make sure that all of your fingers are in their proper positions before playing the piece to avoid mistakes. The classic 5-finger position helps a lot in this case. You can also navigate your way through the keyboard by feeling for the black keys using your hands. Remember that if you feel for the black keys, you have C, D, and E nested around the “twins” and F, G, A, and B around the “triplets”.` Looking for a new keyboard? Check out this article.

- Practice sight reading with a metronome over a slow, steady, and manageable tempo. Most of the time, you make mistakes when the tempo is too fast.

How To Go Forward From Here

While there are tons more to talk about when learning how to read piano sheet music, these should give you plenty to get started.

While there are tons more to talk about when learning how to read piano sheet music, these should give you plenty to get started.

Remember to take things slow, one step at a time. Eventually, your skills will grow with consistent practice.

To learn more, there are plenty of music theory and sight reading resources you can grab online via a simple Google search.

You can also use various apps like Sight Reading Factory and Synthesia to augment learning how to read piano sheet music.

I hope you enjoyed this lesson.

If you have any comments, questions, things I might have missed, or suggestions for the next lesson, feel free to let me know.

Have fun practicing.